Get the slides

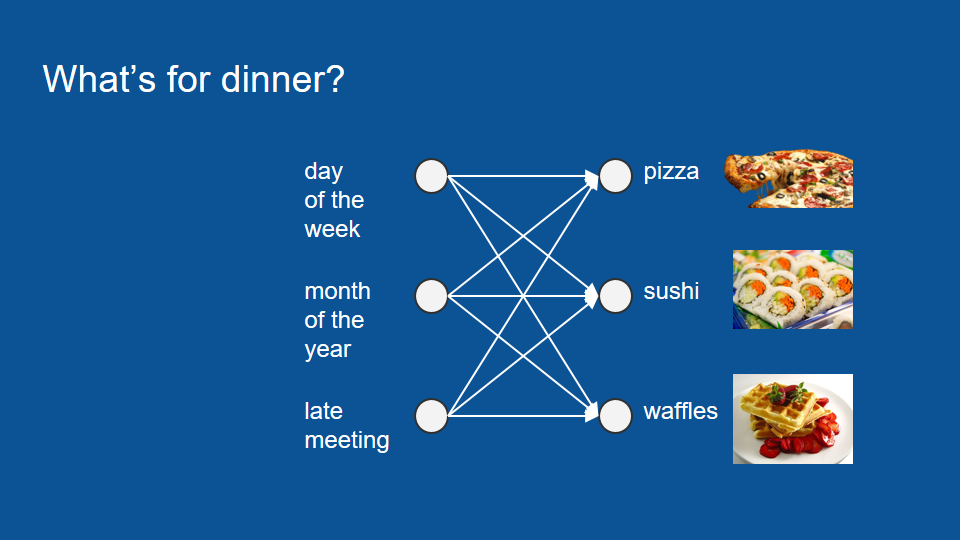

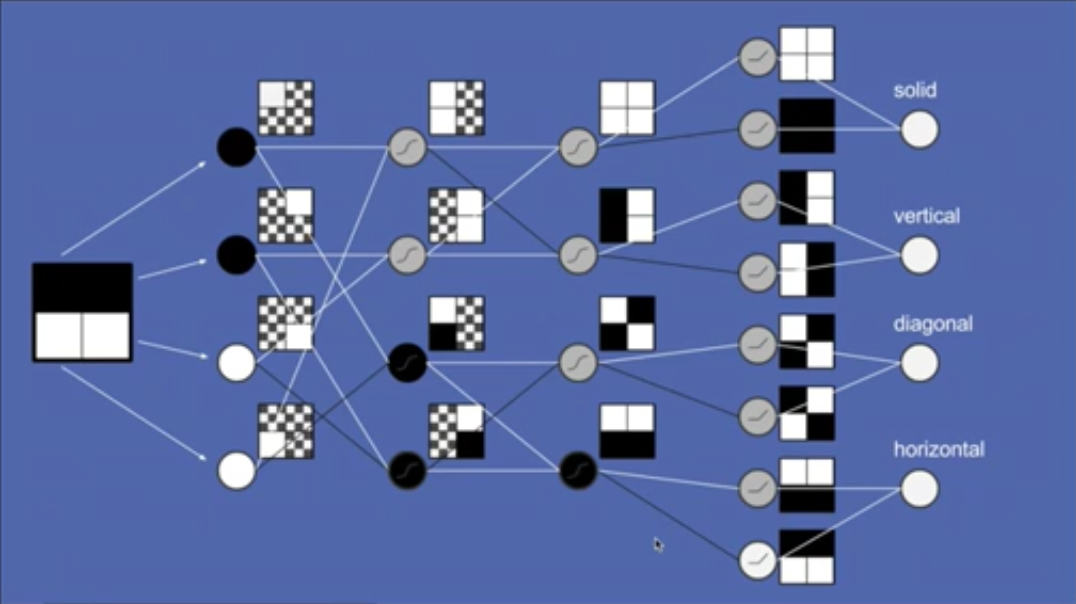

Applications of machine learning have gotten a lot of traction in the last few years. there's a couple of big categories that have had wins. One is identifying pictures, the equivalent of finding cats on the Internet and any problem that can be made to look like that and the other is sequence to sequence translation. This can be speech to text or one language to another. Most of the former are done with convolutional neural networks, most of the latter are done with recurrent neural networks, a particularly long short-term memory. To give an example of how long short-term memory works we will consider the question of what's for dinner. Let’s say for a minute that you are a very lucky apartment dweller and you have a flatmate who loves to cook dinner. Every night he cooks one of three things sushi, waffles or pizza and you would like to be able to predict what you're going to have on a given night. So you can plan the rest of your days eating accordingly. In order to predict what you're going to have for dinner you set up a neural network. The inputs to this neural network are a bunch of items like the day of the week, the month of the year, whether or not your flatmate within a late meeting. Variables that might reasonably affect what you're going to have for dinner.

Now if you're new to neural networks I highly recommend you take a minute and stop to watch the how neural networks work tutorial. There’s a link down in the comments section.

if you'd rather not do that right now and you're still not familiar with neural networks you can think of them as a voting process and so in the neural network that you set up there's a complicated voting process and all of the inputs like day of the week and month of the year go into it and then you train it on your history of what you've had for dinner and you learn how to predict what's going to be for dinner tonight. The trouble is that your network doesn't work very well. Despite carefully choosing your inputs and training it thoroughly, you still can't get much better than chance predictions on dinner.

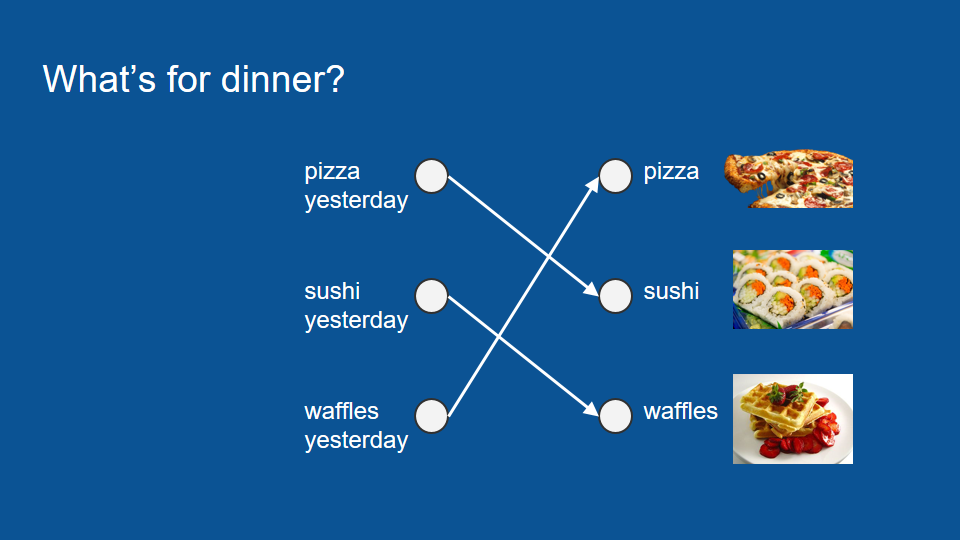

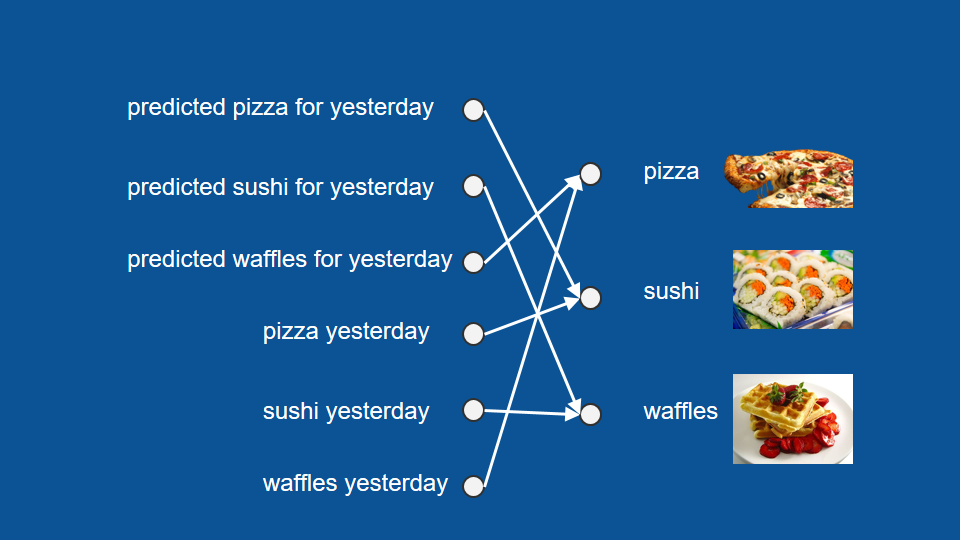

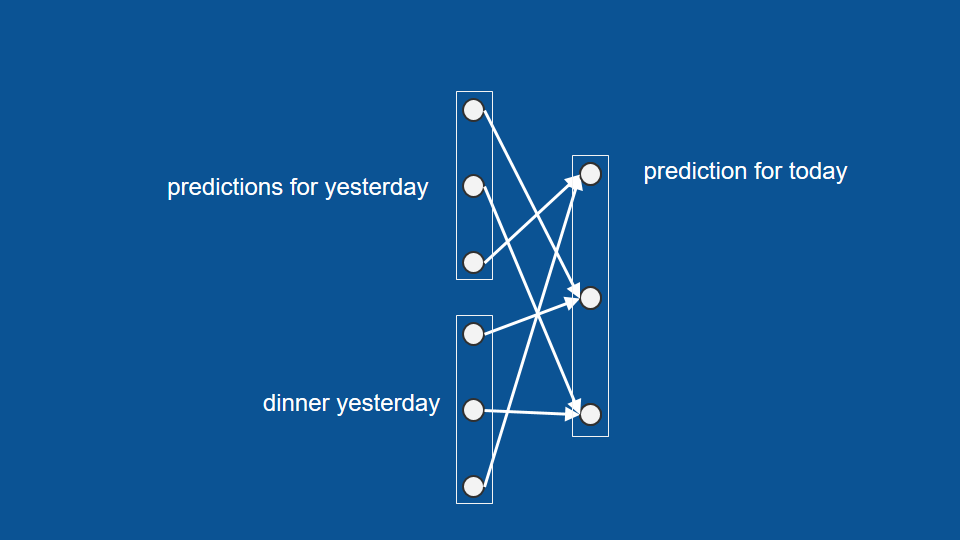

As is often the case with complicated machine learning problems, it’s useful to take a step back and just look at the data and when you do that you notice a pattern. Your flatmate makes pizza then sushi then waffles then pizza again in a cycle. It doesn't depend on the day of the week or anything else, it's in a regular cycle so knowing this, we can make a new neural network. In our new one the only inputs that matter are what we had for dinner yesterday. So we know if we had pizza for dinner yesterday it will be sushi tonight, sushi yesterday waffles tonight, waffles yesterday pizza tonight. It becomes a very simple voting process and its right all the time because you're flatmate is incredibly consistent.

Now if you happen to be gone on a given night, let's say yesterday you were out, you don't know what was for dinner yesterday. You can still predict what's going to be for dinner tonight by thinking back to days ago. Think what was for dinner then so what would be predicted for you last night and then you can use that prediction in turn to make a prediction for tonight.

So we make use of not only our actual information from yesterday but also what our prediction was yesterday.

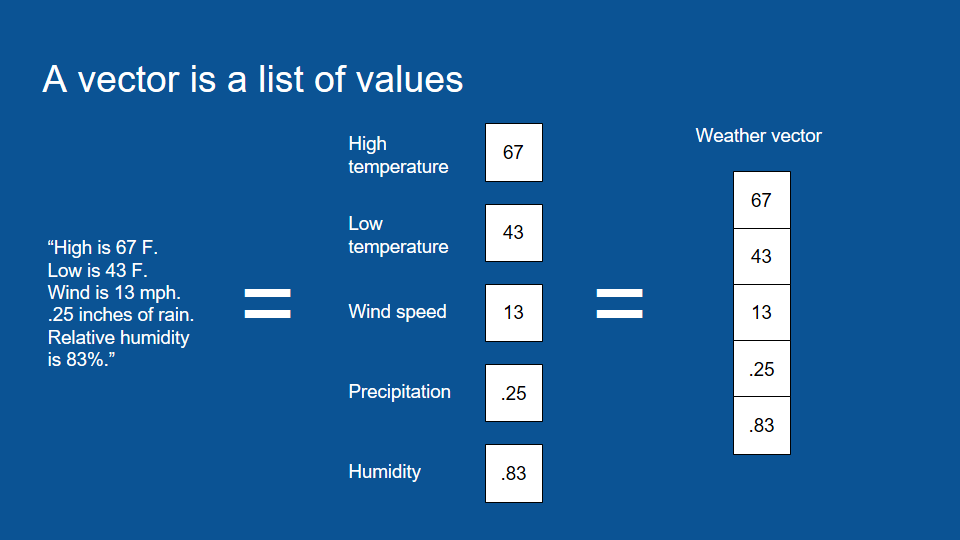

So at this point it's helpful to take a little detour and talk about vectors. A vector is just a fancy word for a list of numbers. If I want to describe the weather to you for a given day I could say the high is 76 degrees Fahrenheit, the low is 43, and the wind is 13 miles an hour, there's going to be a quarter inch of rain and the relative humidity is 83%.

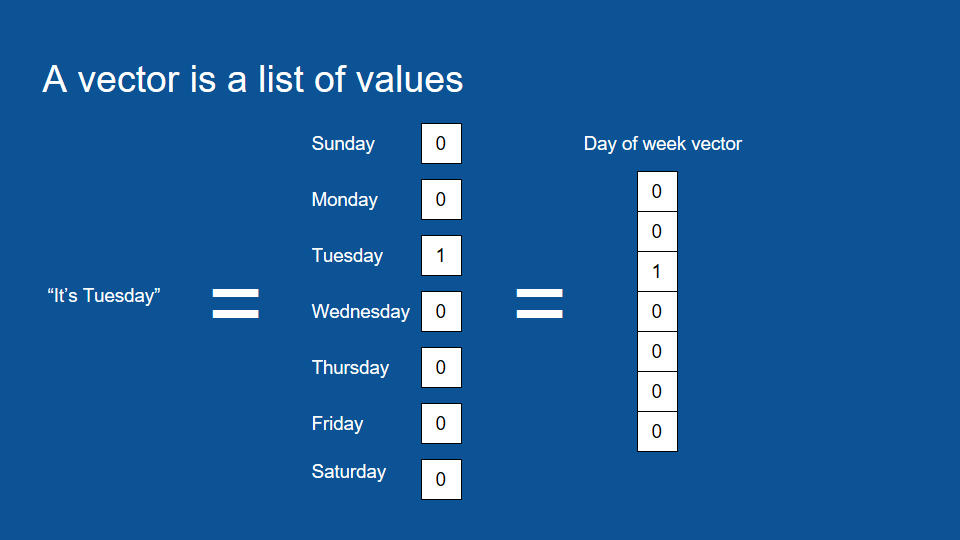

That’s how the vector is. The reason that it's useful is vectors -lists of numbers- are computers native language. If you want to get something into a format that it's natural for a computer to compute, to do operations on, to do statistical machine learning, lists of numbers are the way to go. Everything gets reduced to a list of numbers before it goes through an algorithm. We can also have vector for statements like it's Tuesday. In order to encode this kind of information what we do is we make a list of all the possible values that could have in this case, all the days of the week, and we assign a number to each and then we go through and set them all equal to zero except for the one that is true. Right now this format is called one hot encoding and it's very common to see long vector of zeros with just one element being one.

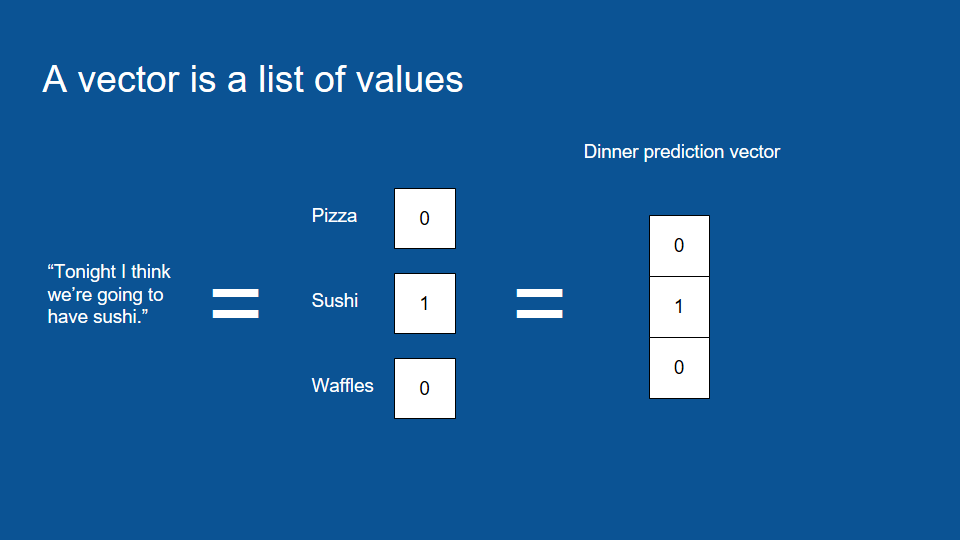

It seems inefficient but for a computer this is a lot easier way to ingest that information so we can make a one hot vector for our prediction for dinner tonight. We set everything equal to zero except for the dinner item that we predict so. In this case we'll be predicting sushi.

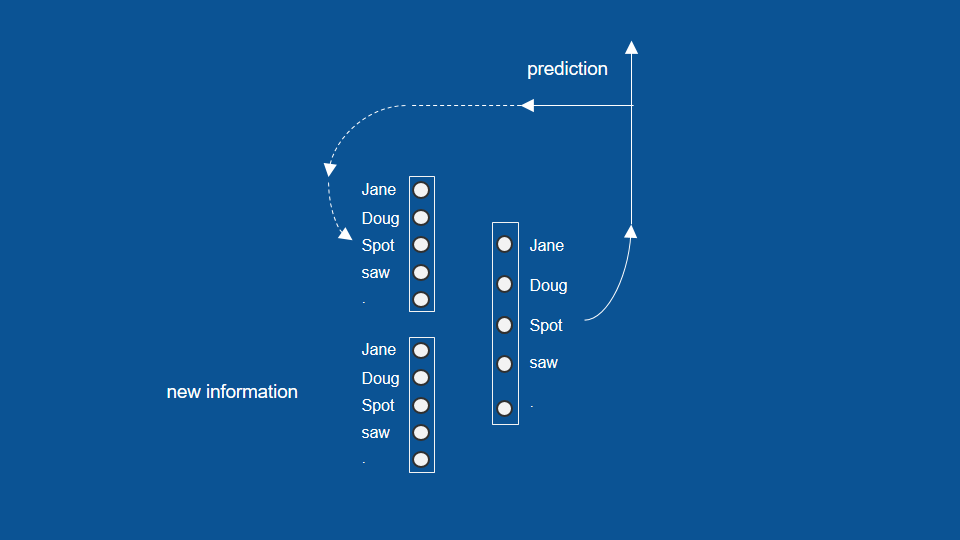

Now we can group together our inputs and outputs into vectors separate lists of numbers and it becomes a useful shorthand for describing this neural network. So we can have our dinner yesterday vector, our predictions for yesterday vector and our prediction for today vector and the neural network is just connections between every element in each of those input vectors to every element in the output vector.

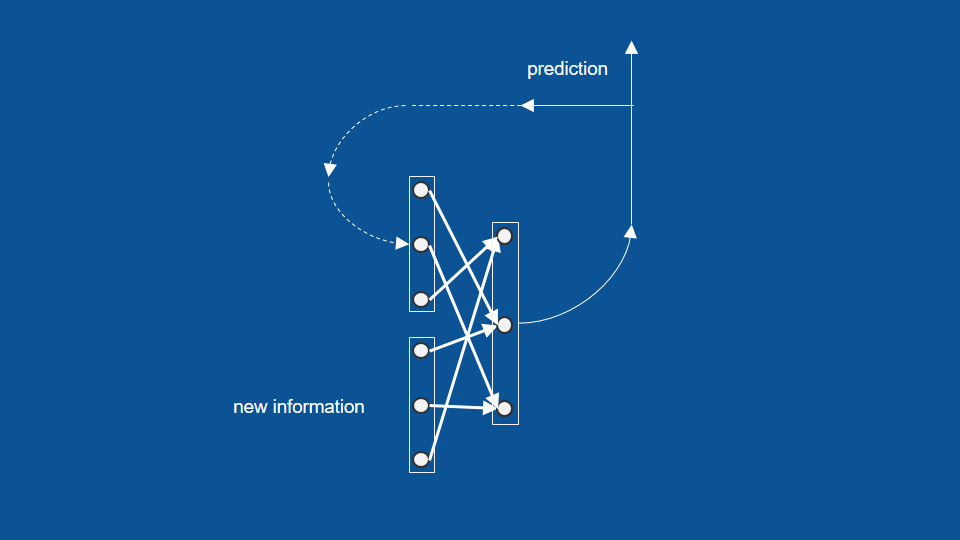

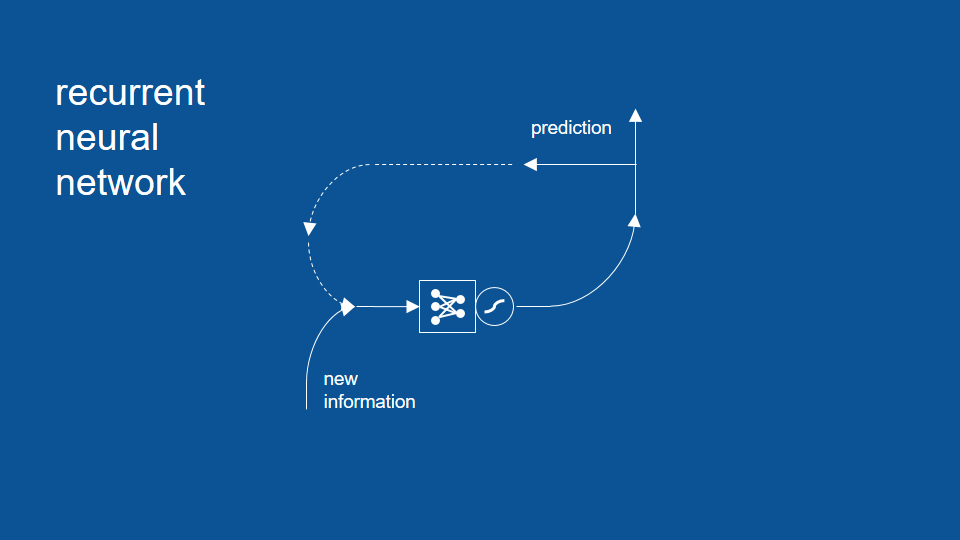

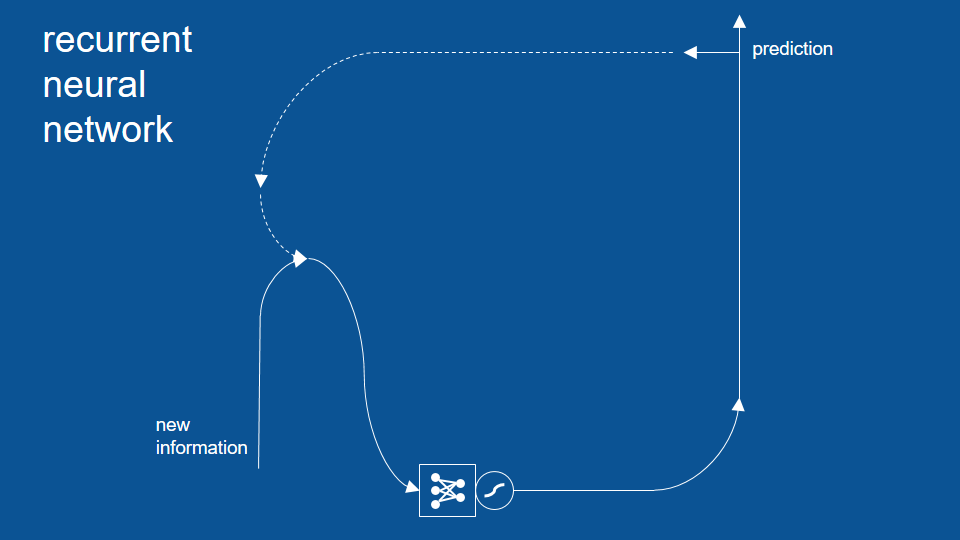

And to complete our picture we can show how the prediction for today will get recycled. The dotted line [there] means hold on to it for a day and then reuse it tomorrow and it becomes our yesterday's predictions tomorrow.

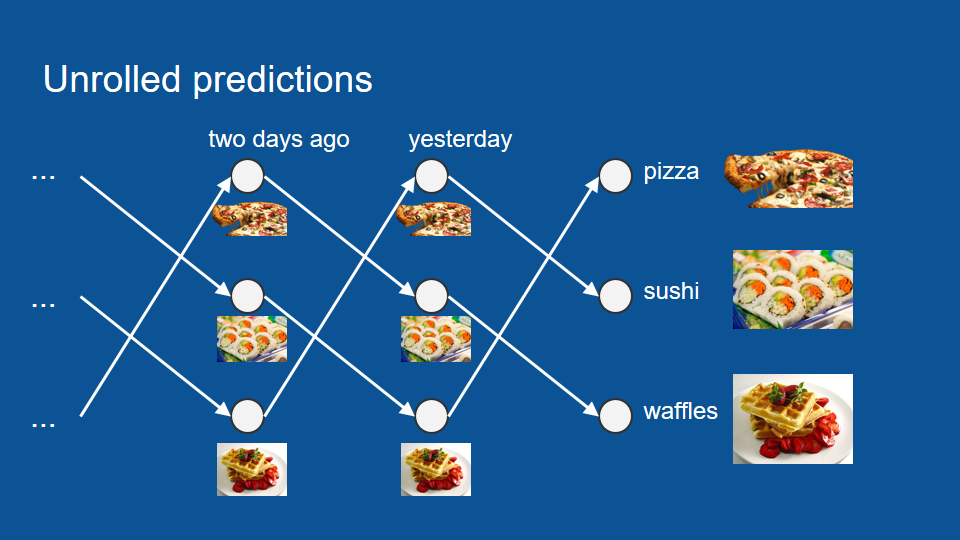

Now we can see how if we were lacking some information, let's say we were out of town for two weeks, we can still make a good guess about what's going to be for dinner tonight we just ignore the new information part and we can unwrap or unwind this vector in time until we do have some information to base it on and then just play it forward and when it's unwrapped, it looks like this (next picture), and we can go back as far as we need to and see what was for dinner and then just trace it forward and play out our menu over the last two weeks until we find out what's for dinner tonight.

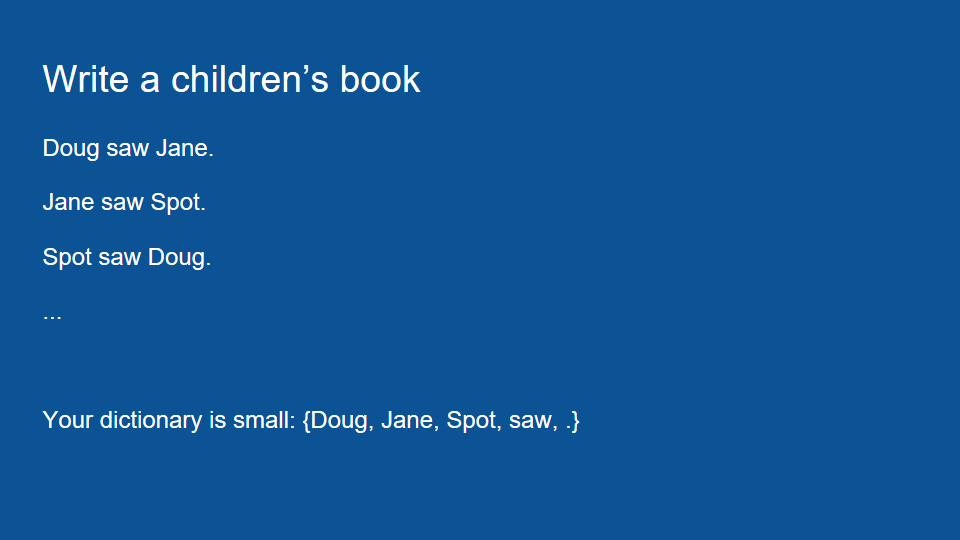

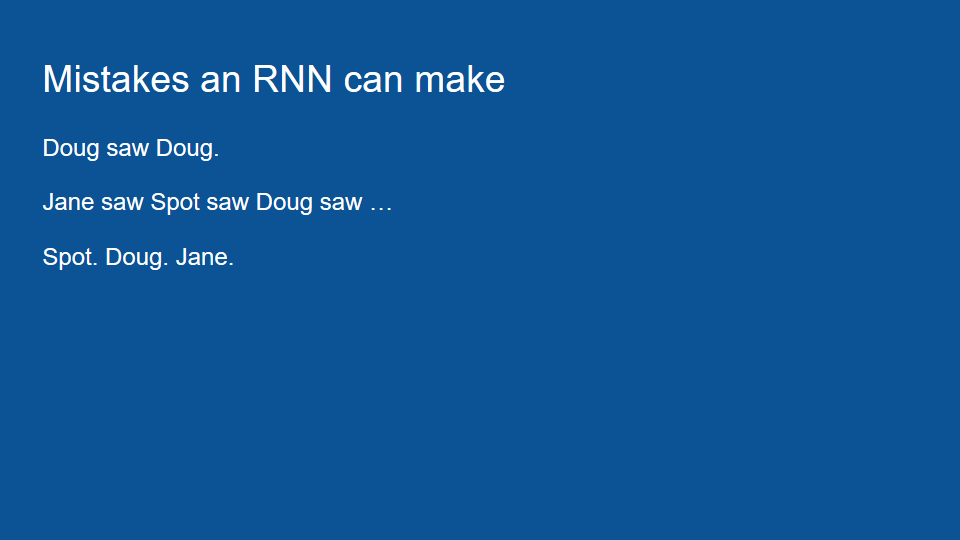

So this is a nice simple example that showed recurrent neural networks. now to show how they don't need all of our needs, we're going to write a children's book, it'll have sentences of the format Doug saw Jane period, Jane saw spot period, spot saw Doug period and so on.

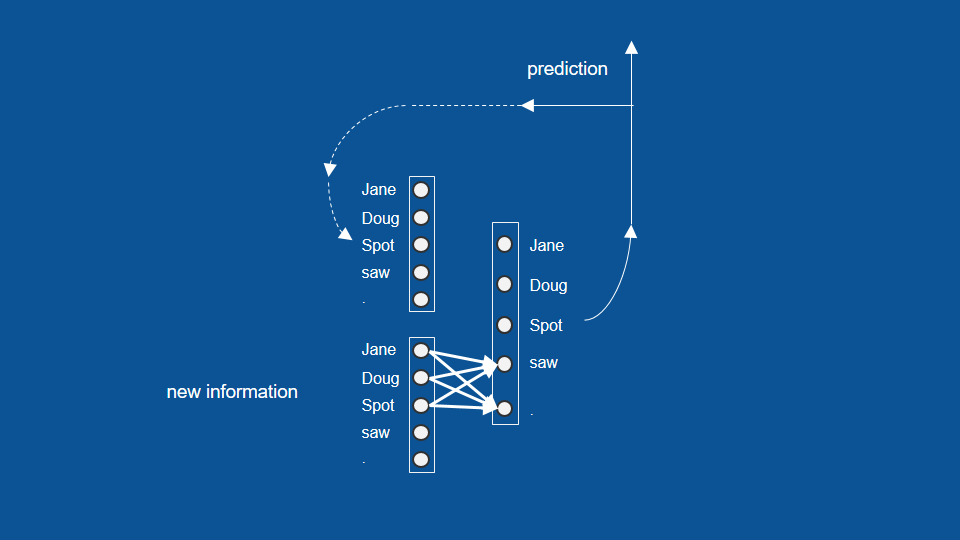

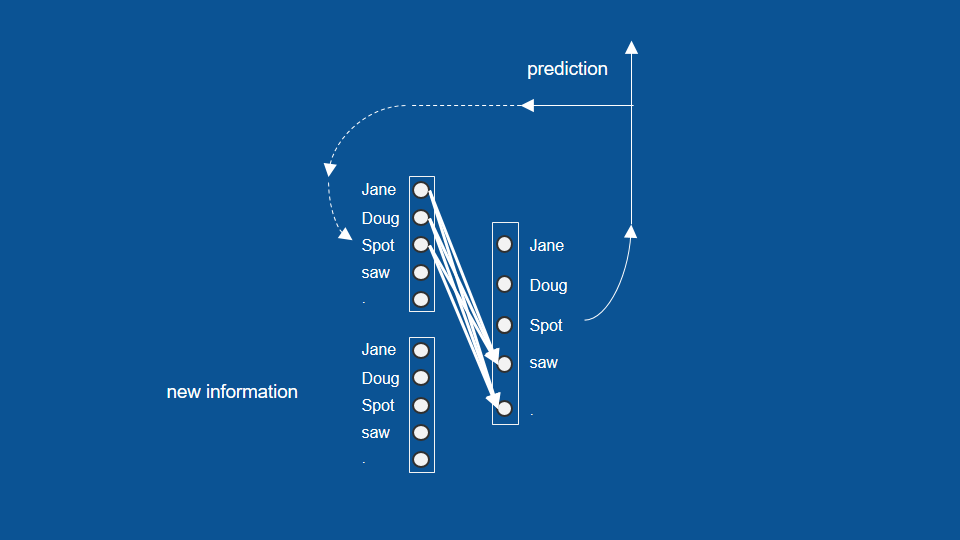

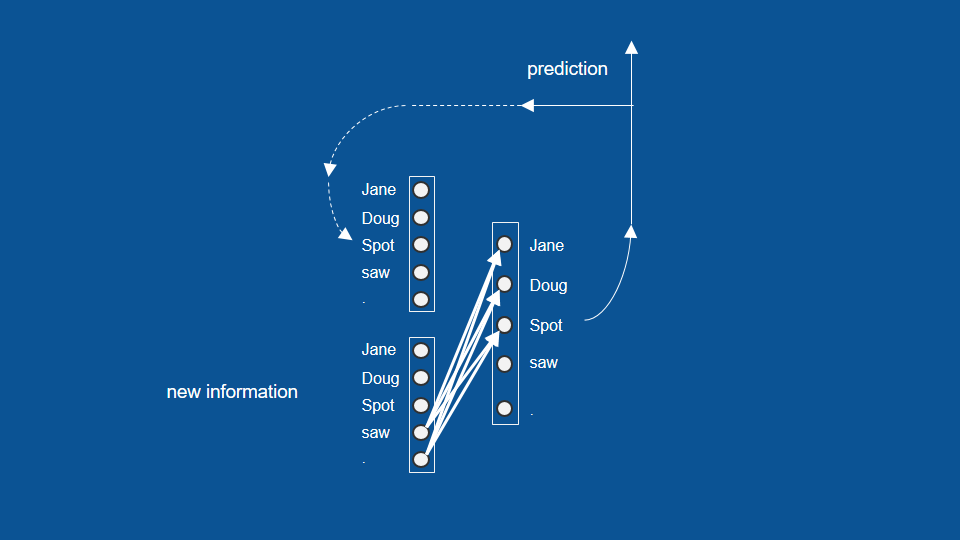

So our dictionary is small. Just the words Doug, Jane, spot, saw, and a period and the task of the neural network has to put these together in the right order to make a good children's book. So to do this we replace our food vectors with our dictionary vectors.

here again it's just a list of numbers representing each of the words so for instance if Doug was the most recent word that I saw, my new information vector would be all zeros except for a one in the Doug position and we similarly can represent our predictions and our predictions from yesterday. now after training this neural network and teaching it what to do we would expect to see certain patterns, for instance, anytime a name comes up Jane, Doug or spot we would expect that to vote heavily for the word saw or for a period because those are the two words in our dictionary that can follow a name.

similarly if we had predicted a name on the previous time step, we would expect those to vote also for the word saw or for a period and then by a similar method, any time we come across the word saw or a period we know that a name has to come after that so it will learn to vote very strongly for a name Jane, Doug or spot.

So in this form, in this formulation we have a recurrent neural network. For simplicity I'll take the vectors and the weights and collapse them down to that little symbol with the dots and the arrows -the dots and the lines connecting them.

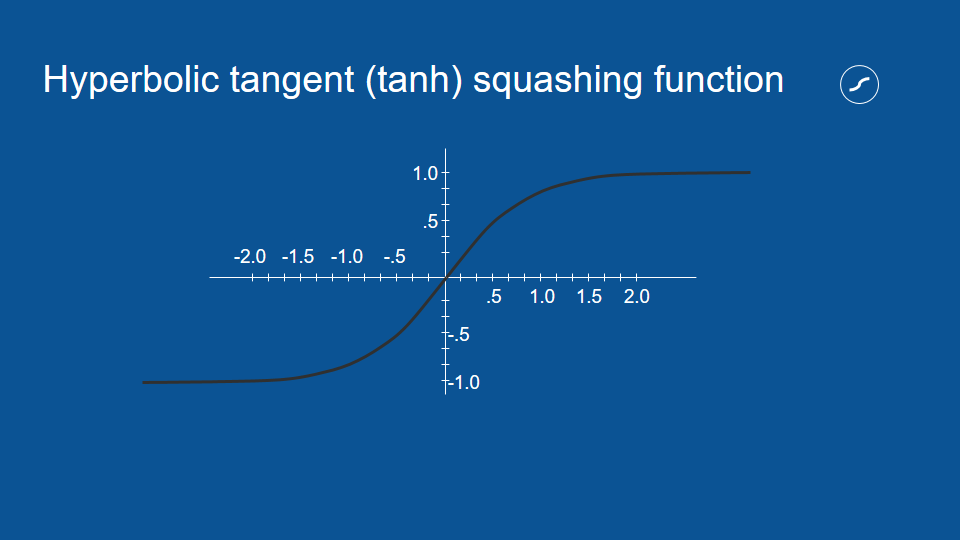

And there's one more symbol we haven't talked about yet. This is a squashing function and it just helps the network to behave.

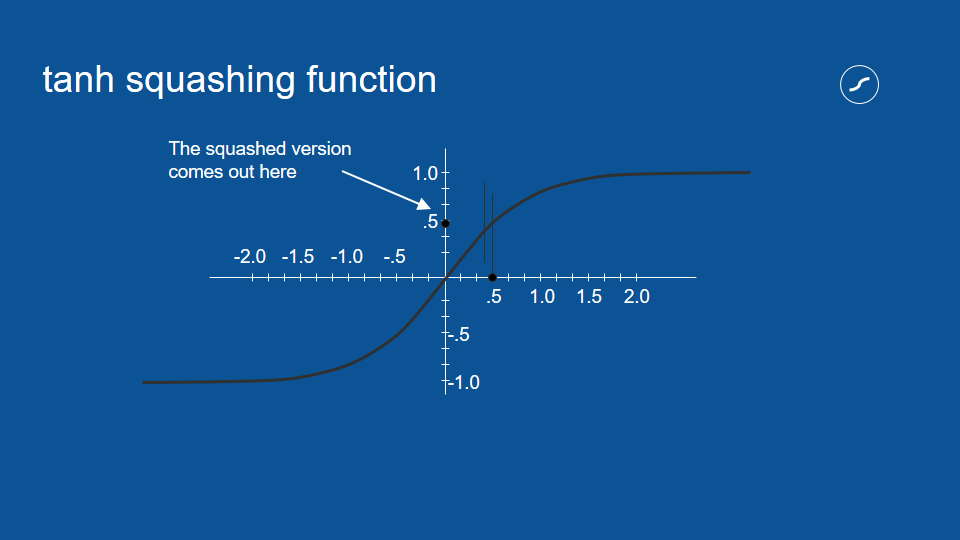

how it works is you take all of your votes coming out and you subject them to this squashing function, for instance, if something received a total vote of 0.5 you draw a vertical line up where it crosses the function you draw horizontal line over to the y-axis and there is your squashed version out.

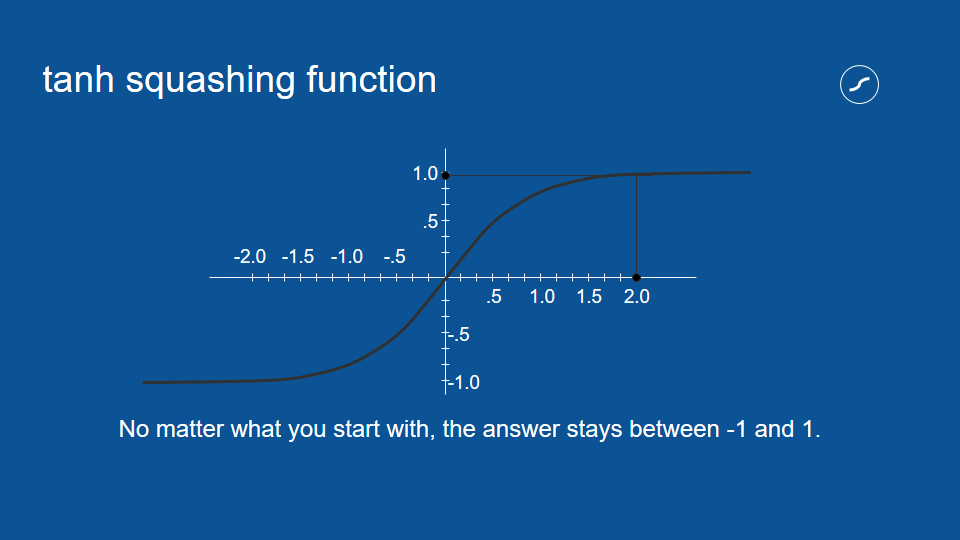

for small numbers the squashed version is pretty close to the original version but as your number gets larger, the number that comes out is closer and closer to one and similarly if you put in a big negative number then what you'll get out will be very close to -1. No matter what you put in what comes out is between -1 and 1.

so this is really helpful when you have a loop like this where the same values get processed again and again day after day, it is possible [you can imagine if] in the course of that processing [say] something got voted for twice, it got multiplied by 2, in that case it would get twice as big every time and very soon blow up to be astronomical. By ensuring that it's always less than 1 but more than -1 you can multiply it as many times as you want you can go through that loop and it won't explode in a feedback loop. This is an example of negative feedback or attenuating feedback.

So you may have noticed our neural network in its current state is subject to some mistakes. we could get a sentence, for instance of the form Doug saw Doug period because Doug strongly votes for the word saw which in turn strongly votes for [I made] any name which could be Doug. Similarly we could get something like Doug saw Jane saw spot saw Doug.

Because each of our predictions only looks back one time step it has very short term memory, then it doesn't use the information from further back and it's subject to these types of mistakes. In order to overcome this we take our recurrent neural network and we expand it and we add some more pieces to it.

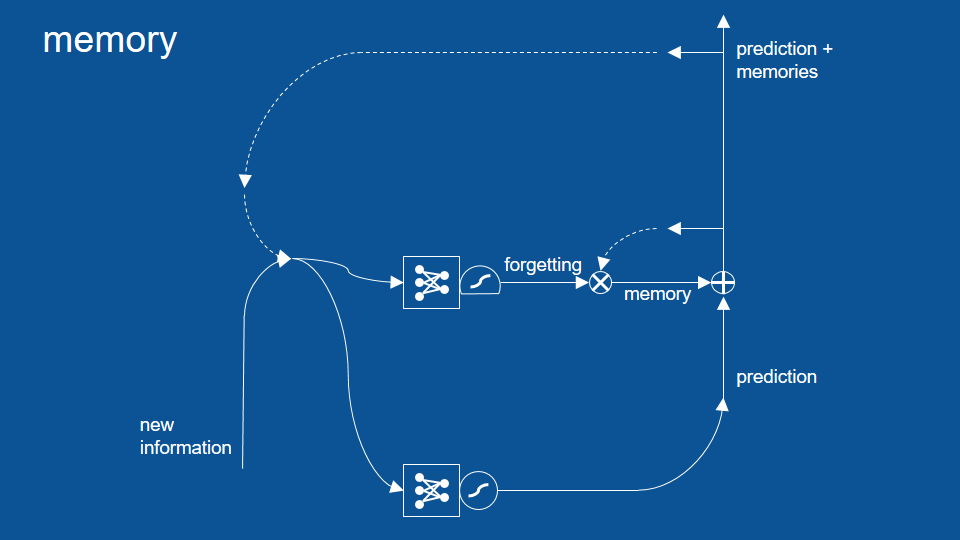

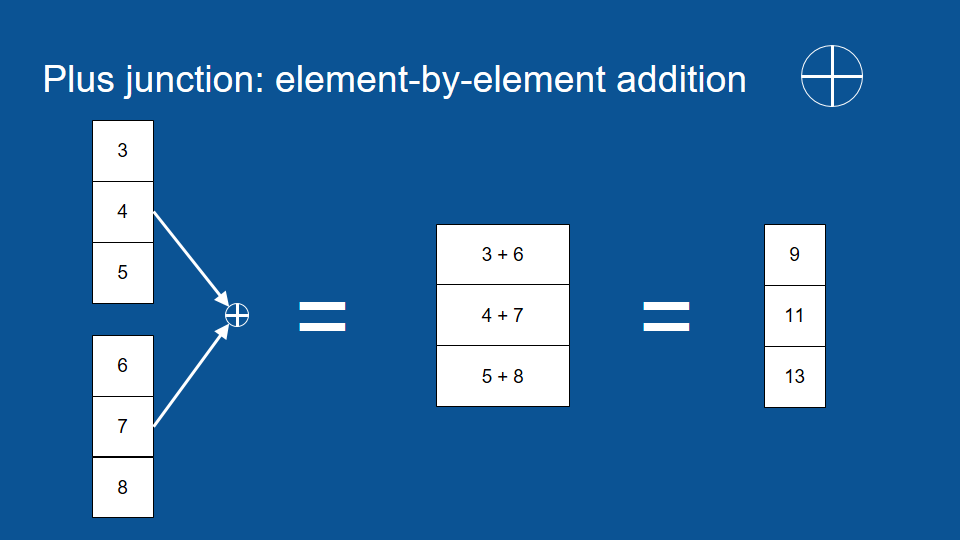

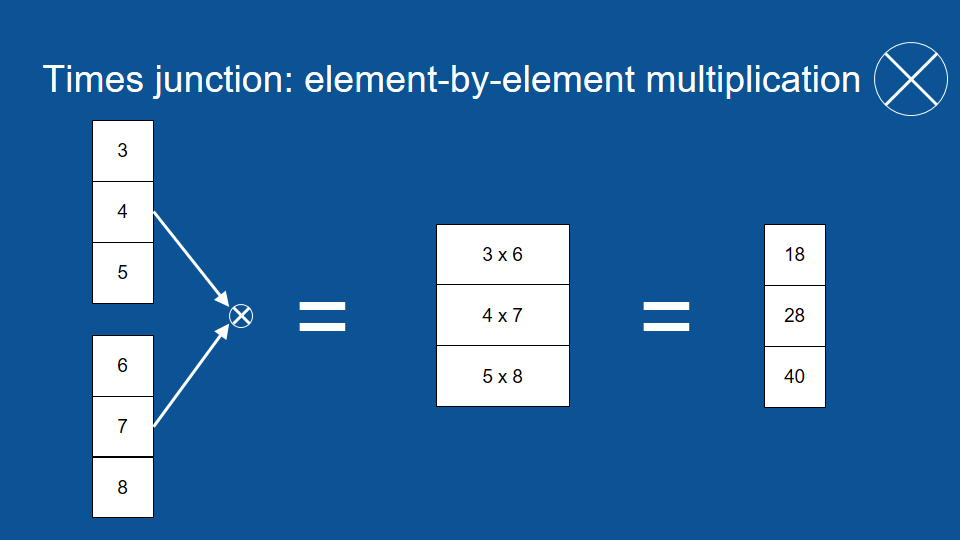

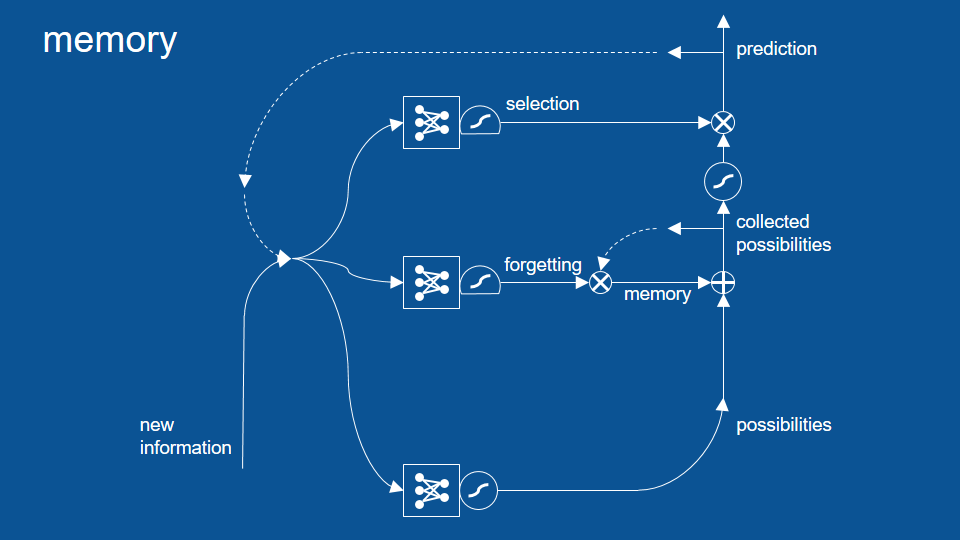

The critical part that we add to the middle here is memory. We want to be able to remember what happened many time steps ago. So in order to explain how this works I'll have to describe a few new symbols that we've introduced here. One is another squashing function -the one with a flat bottom- one is an X in a circle and one is a cross in a circle. So the cross in a circle is element by element addition the way it works is you start with two vectors of equal size and you go down each one, you add the first element of one vector to the first element of another vector and then the total goes into the first element of the output vector.

so three plus six equals nine, then you go to the next element four plus seven equals eleven and so your output vector is the same size of each of your input vectors -just a list of numbers same length- but it's the sum, element by element, of the two and very closely related to this. You’ve probably guessed the X in the circle is element by element multiplication. It’s just like addition except instead of adding you multiply, for instance, three times six gives you a first element of 18, four times seven gets you 28. Again the output vector is the same size of each of the input vectors.

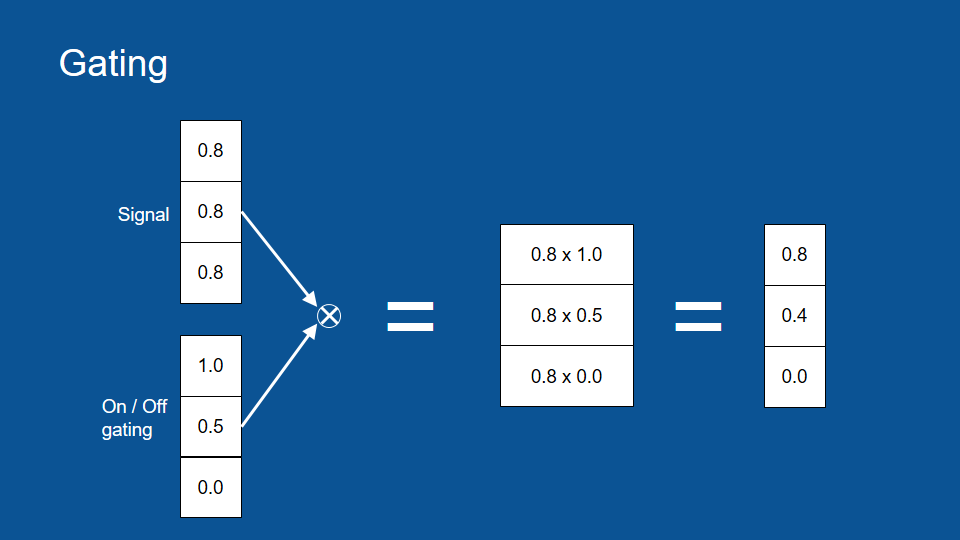

Now element wise multiplication lets you do something pretty cool. Imagine that you have a signal and it's like a bunch of pipes and they have a certain amount of water trying to flow down them, in this case we'll just assign a number to data, 0.8.

now on each of those pipes we have a faucet, we can open it all the way, close it all the way or keep it somewhere in the middle to either let that signal come through or block it. so in this case an open gate -an open faucet- would be a 1 and a closed faucet would be a zero and the way this works with element-wise multiplication, we get 0.8 times one equals 0.8 that signal passed right through into the output vector but the last element 0.8 times zero equals zero. that signal -the original signal- was effectively blocked and then with the gating value of 0.5 the signal was passed through but it's smaller, it's attenuated, so gating lets us control what passes through and what gets blocked which is really useful now.

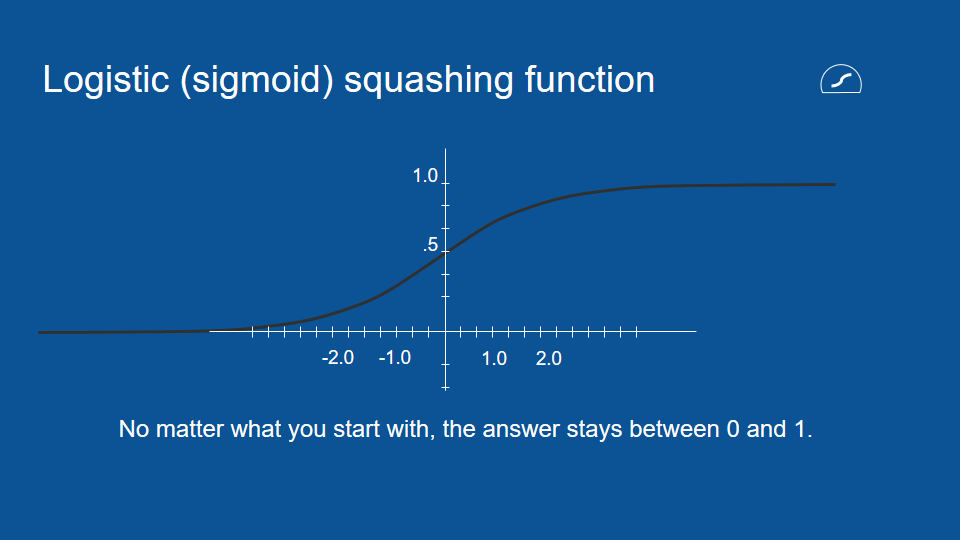

In order to do gating it's nice to have a value that you know is always between zero and one so we introduce another squashing function. this will represent with a circle with a flat bottom and it's called the logistic function, it's very similar to the other squashing function -the hyperbolic tangent- except that it just goes between zero and one instead of minus one and one.

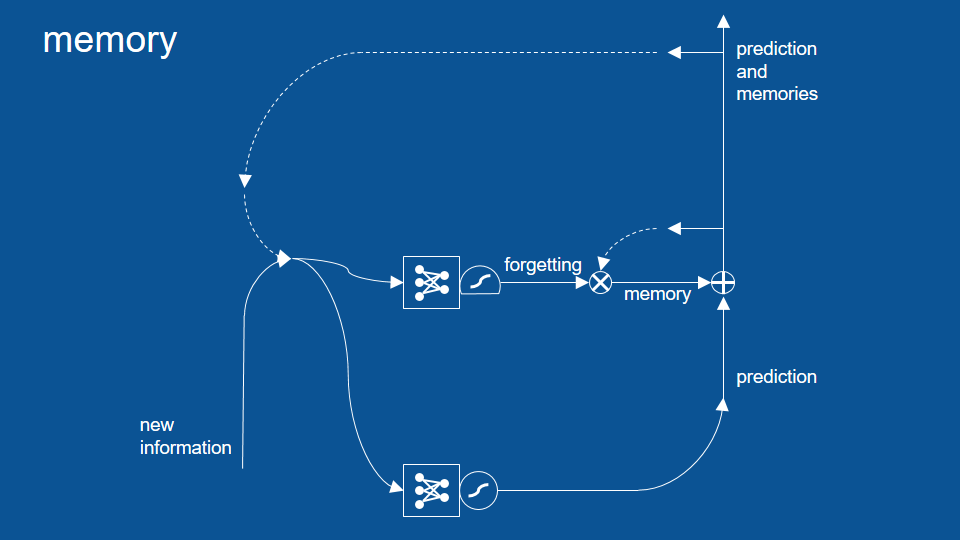

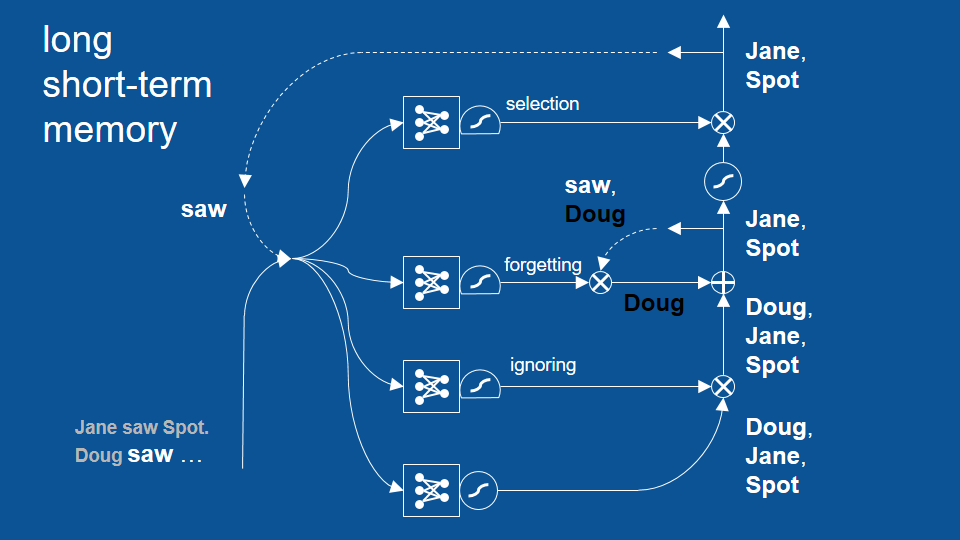

Now when we introduce all of these together what we get we still have the combination of our previous predictions and our new information. Those vectors get passed and we make predictions based on them. those predictions get passed through but the other thing that happens is a copy of those predictions is held on to for the next time step -the next pass through the network- and some of them are forgotten here's a gate right here (He points to the multiplication function), some of them are remembered. The ones that are remembered are added back into the prediction.

So now we have not just prediction but predictions plus the memories that we've accumulated and that we haven't chosen to forget yet. Now there's an entirely separate neural network here that learns when to forget, what based on, what we're seeing right now, what do we want to remember and what do we want to forget. So you can see this is powerful. This will let us hold on to things for as long as we want. Now you've probably notice though when we are combining our predictions with our memories we may not necessarily want to release all of those memories out as new predictions each time. So we want a little filter to keep our memories inside and let our predictions get out and that's we add another gate for that to do selection.

it has its own neural network -so its own voting process- so that our new information and our previous predictions can be used to vote on what all the gates should be, what should be kept internal and what should be released as a prediction. we've also introduced another squashing function here .since we do an addition here it's possible that things could become greater than 1 or smaller than -1, so we just squash it to be careful to make sure it never gets out of control and now when we bring in new predictions we make a lot of possibilities and then we collect those with memory over time and of all of those possible predictions at each time step we select just a few to release as the prediction for that moment. Each of these things, when to forget and when to let things out of our memory, are learned by their own neural networks.

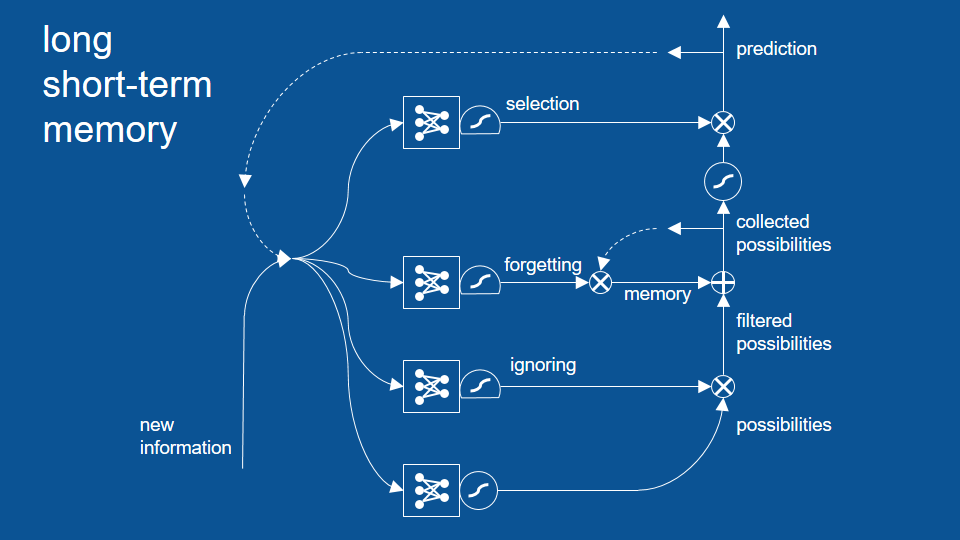

And the only other piece we need to add to complete our picture here is yet another set of gates. This lets us actually ignore possible predictions -possibilities as they come in. this is an intention mechanism. It lets things that aren't immediately relevant be set aside so they don't cloud the predictions in memory going forward. It has its own neural network and its own logistics some function and its own gating activity [right here].

now long short-term memory has a lot of pieces -a lot of bits that work together- and it's a little much to wrap your head around it all at once, so what we'll do is take a very simple example and step through it just to illustrate how a couple of these pieces work. It admittedly an overly simplistic example and feel free to poke holes at it later. When you get to that point then you know you're ready to move on to the next level of material.

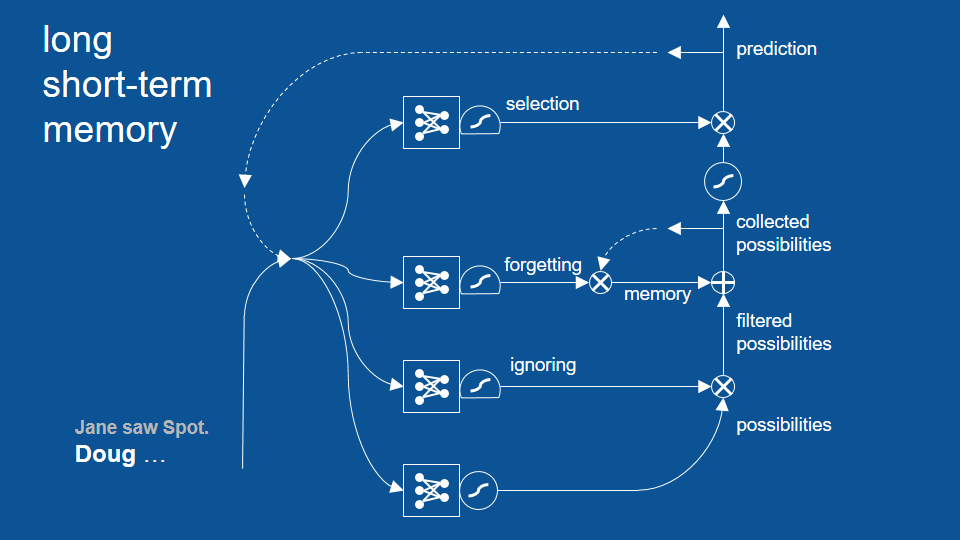

So we are now in the process of writing our children's book and for the purposes of demonstration we will assume that this LSTM has been trained on our children's books examples that we want to mimic and all of the appropriate votes and weights in those neural networks have been learned. Now we'll show it in action.

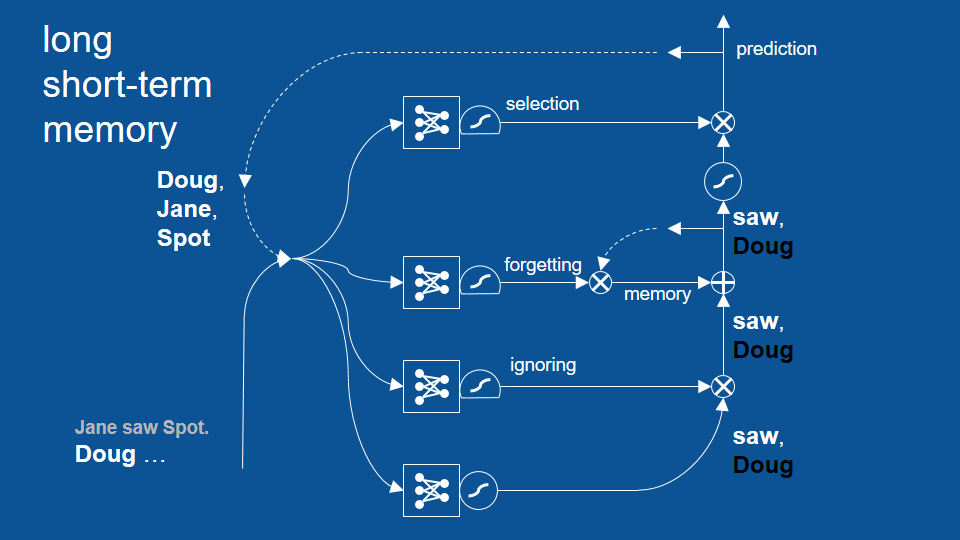

our story so far is Jane saw spot period, Doug … so Doug is the most recent word that's occurred in our story and also not surprisingly for this time step the names Doug, Jane and spot were all predicted as viable options. This makes sense we had just wrapped up a sentence with a period the new sentence can start with any name so these are all great predictions so we have our new information which is the word Doug. We have our recent prediction which is Doug, Jane and spot and we passed these two vectors together to all four of our neural networks which are learning to make predictions to do ignoring, to do forgetting and to do selection.

So the first one of these make some predictions. given that the word Doug just occurred, this has learned that the word saw is a great guess to make for a next word but it's also learned that having seen the word Doug that it should not see the word Doug again very soon -seeing the word Doug at the beginning of a sentence. So it makes a positive prediction for saw and a negative prediction for dog it says: I do not expect to see Doug in the near future so that's why Doug is in black. So this example is so simple, we don't need to focus on attention or ignoring. So we'll skip over it for now and this prediction of saw not Doug is passed forward and again for the purposes of simplicity, let's say, there's no memory at the moment.

so saw and Doug get passed forward and then the selection mechanism here has learned that when the most recent word was a name then what comes next is either going to be the word saw or a period so it blocked any other names from coming out so the fact that there's a vote for not Doug gets blocked here and the word saw gets sent out as the prediction for the next time step. So we take a step forward in time now the word saw is our most recent word and our most recent prediction. They get passed forward to all of these neural networks and we get a new set of predictions.

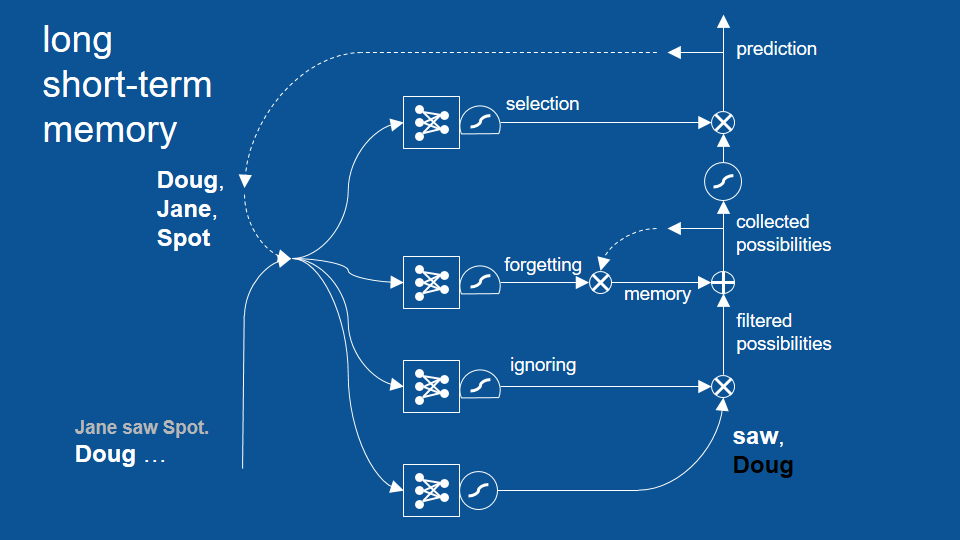

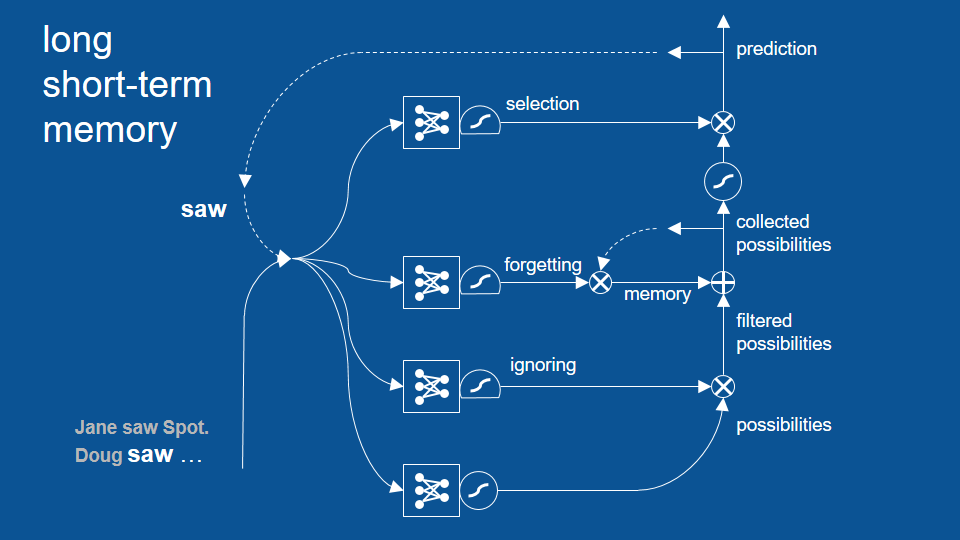

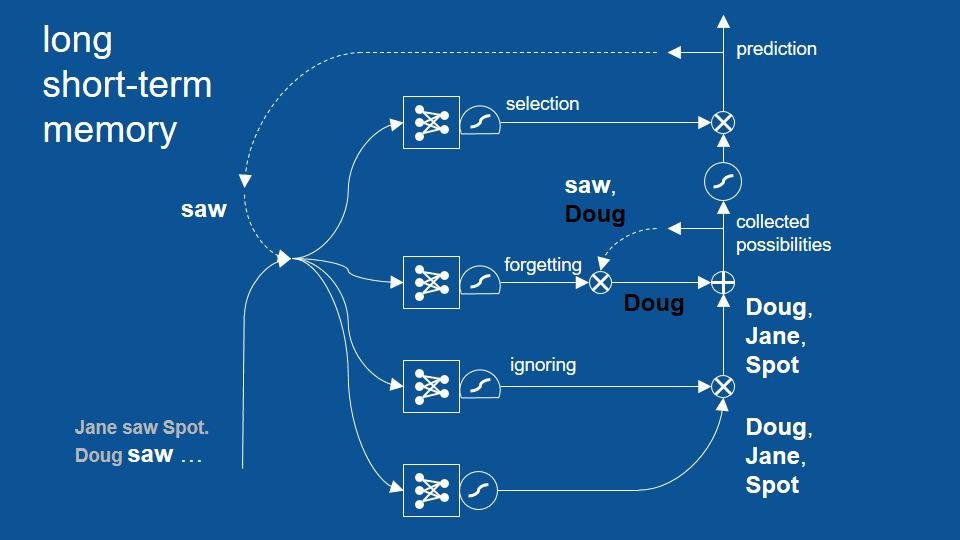

Because the word saw just occurred we now predict that the words Doug, Jane or spot might come next we will pass over ignoring and attention in this example and we'll take those predictions forward.

Now the other thing that happened is our previous set of possibilities. The word saw and not Doug that we were maintaining internally get passed to a forgetting gate. now the forgetting gate says: hey my last word that came -that occurred- was the word saw based on my past experience then I can forget about, [you know I know that it occurred] I can forget that it happened but I want to keep any predictions having to do with names so it forgets saw, holds on to the vote for not Doug and now at this element by element addition we have a positive vote for Doug a negative vote for Doug and so they cancel each other out. So now we just have votes for Jane and spots. Those get passed forward.

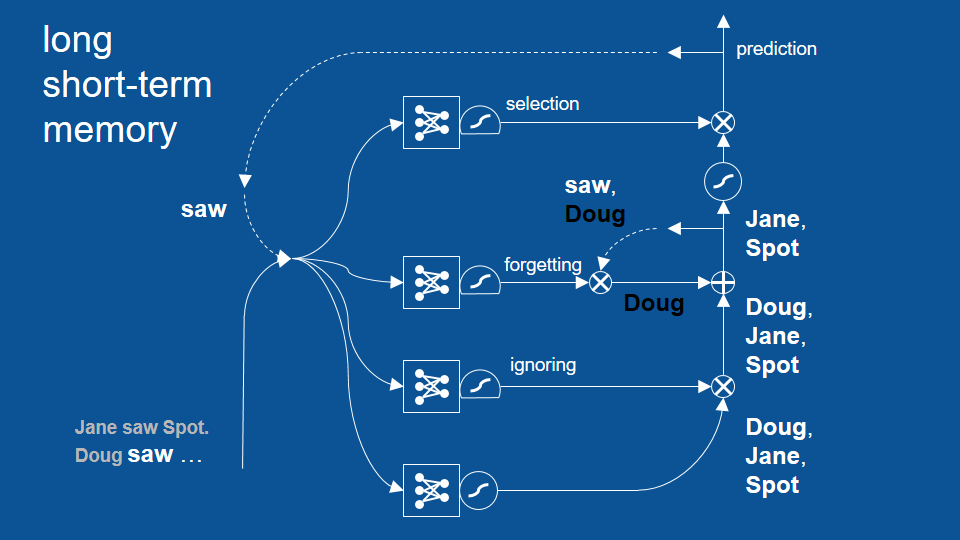

Our selection gate it knows that the word saw just occurred and based on experience a name will happen next and so it passes through these predictions for names and for the next time step then we get predictions of only Jane and spot not Doug.

This avoids the Doug saw Doug period type of error and the other errors that we saw. What this shows is that long short-term memory can look back two, three, many time steps and use that information to make good predictions about what's going to happen next. Now to be fair to vanilla recurrent neural networks they can actually look back several time steps as well but not very many. LSTM can look back many time steps and has shown that successfully.

This is really useful in some surprisingly practical applications. If I have text in one language and I want to translate it to text to another language, LSTM's work very well. even though translation is not a word to word process, it's a phrase to phrase or even in some cases a sentence to sentence process, LSTMS are able to represent those grammar structures that are specific to each language and what it looks like is that they find the higher-level idea and translate it from one mode of expression to another, just using the bits and pieces that we just walked through.

Another thing that they do well is translating speech to text. Speech is just some signals that vary in time. It takes them and uses that then to predict what text -what word- is being spoken and it can use the history -the recent history of words- to make a better guess for what's going to come next. LSTMS are a great fit for any information that's embedded in time –like audio, video- on my favorite application of all of course is robotics. Robotics is nothing more than an agent taking in information from a set of sensors and then based on that information, making a decision and carrying out an action. It’s inherently sequential and actions taken now can influence what is sensed and what should be done many times steps down the line.

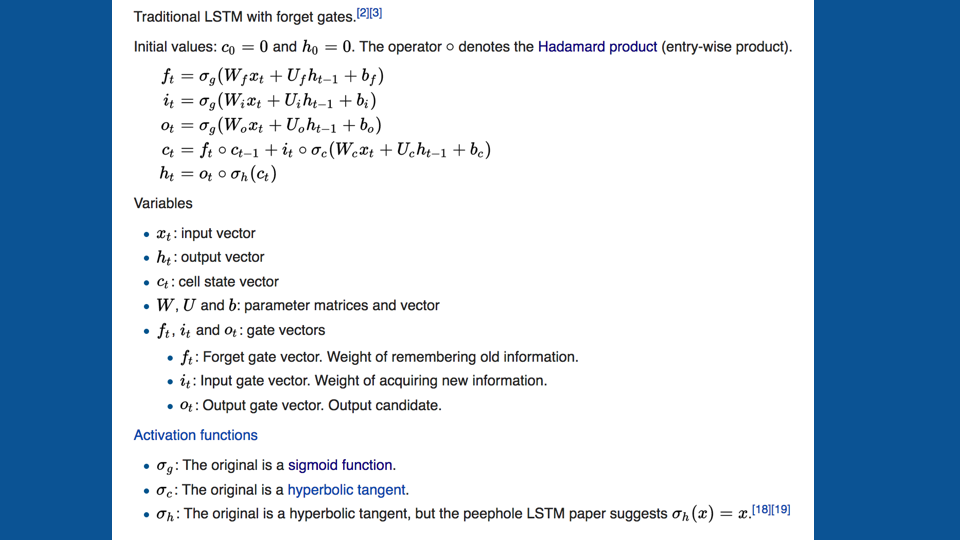

If you're curious what LSDM’s look like in math this is it (next picture). This is lifted straight from the Wikipedia page.

I won't step through it but it's encouraging that something that looks so complex expressed mathematically can actually makes a fairly straightforward picture and story and if you'd like to dig into it more I encourage you to go to the Wikipedia page also there are a collection of really good tutorials and discussions, other ways of explaining LSDM’s that you may find helpful as well.

Resources

- Chris Olah's tutorial

- Andrej Karpathy's

- Blog post

- RNN code

- Stanford CS231n lecture

- The DeepLearning 4J tutorial has some helpful discussion and a longer list of good resources.

- How Neural Networks Work[video]

I'd also strongly encourage you to visit Andrej karpathy blog posts showing examples of what LSDM’s can do in text and if you haven't seen it yet take a look at the video on how neural networks work to get some more details on exactly how you go about implementing something like this in code.

Thanks for tuning in, I wish you a lot of luck on your next project building with recurrent neural networks.